24 July 2024

I begin by acknowledging the Traditional Owners of the land on which we meet, the Dharug people, and pay respect to their Elders, past, present and emerging.

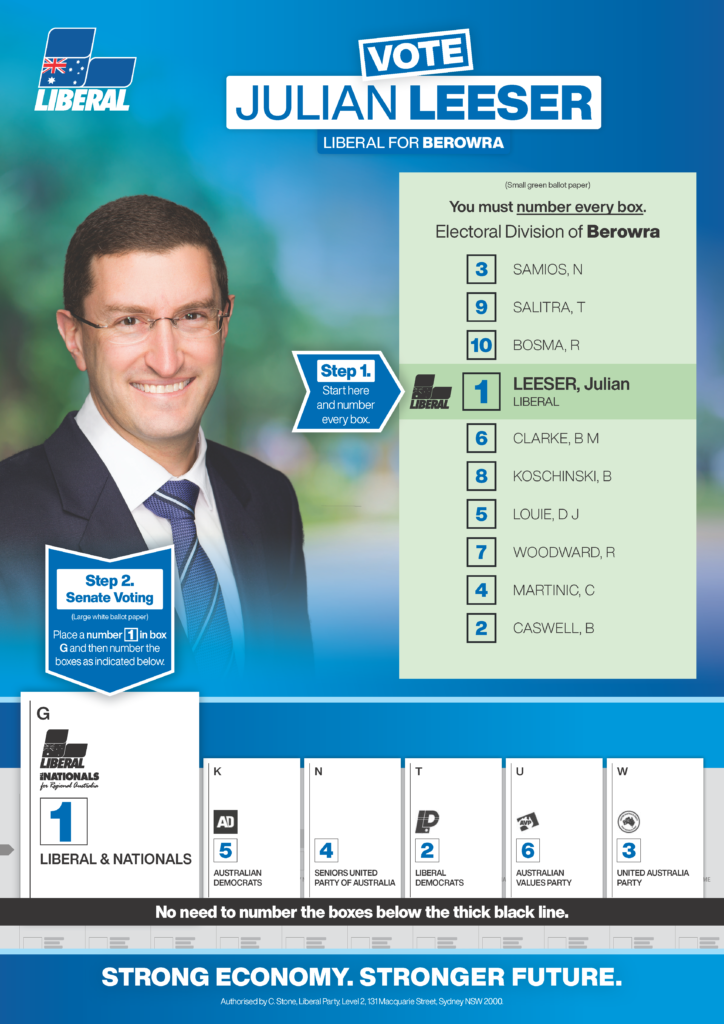

This is the first event I have been invited to address in the Epping community since the Electoral Commissioner’s announcement that this part of Epping might become part of the Berowra electorate. And I’m excited to have the opportunity to represent this vibrant part of Sydney.

I would like to acknowledge Mayor Philip Ruddock, a distinguished former Minister for Indigenous Affairs.

I would also like to acknowledge John Lochowiak, the Chair of the National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Catholic Council.

John’s leadership exemplifies the care and concern that the Catholic Church has long taken in the welfare of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians.

In particular, I would like to acknowledge the honour my friend, Bishop Anthony Randazzo, has afforded me in asking me to speak to you tonight.

Bishop Anthony’s commitment to reconciliation is very personal and is to some extent informed by Indigenous members of his own family.

Although tonight I will talk about the journey of Australians to Indigenous reconciliation, I wanted to mention one other form of reconciliation this evening that relates to my friendship with Bishop Anthony.

As a Jewish Australian, I rejoice in my friendship with Catholic Australians who have done so much to enrich my own life.

I was proud to have spent four wonderful years working at Australian Catholic University and serving on the board of Mercy Health.

In working for these Catholic institutions, people have occasionally suggested I was hedging my bets in the afterlife.

Through serving both these institutions I acquired a profound appreciation for Catholic social teaching.

Its teachings on human dignity and freedom, compassion for the poor, and justice for all resonate powerfully with me.

These ideals are common to both our faiths. The prophet Micah reminds us to ‘act justly, love mercy, and walk humbly with our God’.

A watershed moment in reconciliation between Jews and Catholics was Nostra Aetate, the 1965 declaration from the

Second Vatican Council that spoke of the Church’s relationship to other faiths.

In Nostra Aetate, the Church declared that ‘the spiritual patrimony common to Christians and Jews’ is ‘so great’.

Cherishing this shared inheritance, the Church ‘decries hatred, persecutions, displays of anti-Semitism, directed against Jews at any time and by anyone’.

I could not come tonight without applauding those leaders in the Australian Catholic Church like Bishop Anthony Randazzo, and his predecessor in Broken Bay, Peter Comensoli, now Archbishop of Melbourne, who have channelled the spirit of Nostra Aetate to condemn anti-Semitism which has sadly been a feature of Australian life since 7 October 2023 and to stand in solidarity with Australia’s Jewish community.

The Hamas terrorist attacks of 7 October and the resultant anti- Semitism which has been unleashed has been a tragedy for this country. Sadly, for the Jewish community, the voices of friends such as Bishop Anthony and Archbishop Peter are not as common as they should be.

In the words of Martin Luther King, ‘In the end, we will not remember the words of our enemies, but the silence of our friends.”

Bishop Anthony has not been silent, and it is an honour to be in his presence tonight.

Reconciliation and the Church

Reconciliation is an inherently Christian concept. As the Anglican Archbishop of Sydney Kanishka Rafael wrote:

Reconciliation is a central theme of the Bible, and a key way of describing God’s work through Jesus to bring peace between us and God, and between peoples. The Bible often connects the saving, reconciling work of God with the restored relationships that we should seek with each other.’

The Catholic Church has always been at the forefront of the reconciliation movement. It was one of the first Churches to back the National Apology to the Stolen Generations.

In 1986 Pope St John Paul II gave a famous address to the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people where he referred to the past injustices sustained by Indigenous Australians and the need to remedy these wrongs, John Paul II told them that:

‘Certainly, what has been done cannot be undone. But what can now be done to remedy the deeds of yesterday must not be put off till tomorrow’.

John Paul’s words remain as true today as they were then.

Reflections on the referendum

Friends, it is now ten months since the referendum. As you know I supported the Voice.

I saw it as a practical way of addressing some of the very real challenges Indigenous Australians face. I believe that governments make better policy when they consult the people directly affected by their decisions.

The majority of Australians did not agree with recognising Indigenous Australians in the Constitution through a Voice, and I respect the decision of the Australian people.

Constitutional recognition through the Voice is not coming back and I don’t seek to reagitate for it.

In the wake of an election defeat, there are usually periods of reflection and listening in political parties and a period of internal discussion about next steps forward.

I’m not aware that there has been any similar discussion or reflection undertaken on why the referendum failed.

I believe there are three fundamental reasons why the referendum failed.

The first is that the Government was overconfident of the success of the referendum. Support for constitutional recognition at the time of the 2022 election was at nearly 80%.

The last national vote was the marriage postal survey which was carried 62% with healthy majorities in each State – so, the thinking went, perhaps the usual rules about referenda would not apply.

In addition, the Labor Government had been returned to office with a majority in its own right for the first time in 12 years and the Coalition had been reduced to 58 seats out of 151 in the House of Representatives.

In the 2022 election campaign, Labor committed to holding a referendum on the Voice.

I think they did so without understanding where the design process was up to, what the Voice really involved and what would be necessary to bring about both an Indigenous consensus and a bipartisan consensus for a successful referendum.

While not questioning the personal commitment of leading proponents of the Voice, we should also not discount the politics. At the time it seemed as though the government had an issue where it could not lose. If the referendum passed this would be the first successful referendum proposed by Labor since 1946. If the referendum failed, the government thought it could just blame the Opposition so that it would win either way.

Prior to the 2022 election, the political consensus was that the worst thing that could happen would be to hold a referendum on recognition that failed.

After the 2022 election, the government’s thinking was that the worst thing was not to try regardless of the outcome. This was best expressed in the repeated quotation of the line from the Jewish Sage Hillel: “If not now, then when?”

This overconfidence affected every decision the Government made.

Second, former coalition Indigenous affairs minister Ken Wyatt set down a road map. His policy was to follow the Calma-Langton report, which called for the establishment of local and regional voice bodies before a national voice would be established. The Coalition had committed $32 million to establish these local and regional bodies in its last Budget in March 2022.

This roadmap was abandoned by the new government.

The local and regional bodies were always the most popular element of the Voice among Indigenous people. They would have made the greatest difference in the lives of Indigenous people in communities.

The roll out of local and regional bodies would have provided workable examples of how the Voice might work which people would have been able to experience before any national body was established.

All of this was meant to occur before any debate or discussion on the legal form of the Voice was worked out. This was the recommendation Pat Dodson and I set out in our 2018 Joint Select Committee report.

Third, there was no proper process for reaching the necessary consensus on the constitutional amendment to be put to a referendum.

The 2018 Joint Select Committee received 18 different versions of constitutional amendment. The Committee didn’t resolve the issue but said that it should be addressed after the process of codesign was complete.

For a referendum to succeed it needed bipartisan support and overwhelming Indigenous support.

The six week parliamentary committee process established in 2023 to consider the amendment was a sham with too little time to consider the matters properly and Government members refusing to engage in compromise.

There were voices warning that the lack of proper process would lead to failure. Father Frank Brennan wrote to the Prime Minister in November 2023 and repeatedly called for a genuine parliamentary committee to build bipartisan consensus around the wording.

Without some sort of constitutional convention or similar genuine process that brought the range of political constituencies and the breadth of Indigenous leaders to work together on reaching common ground on those words the referendum was unlikely to succeed.

In the end only 39.94% of Australians voted for the Voice with majorities in no states. It was the tenth worst defeat of any referendum since federation. It was almost exactly the same result for changes to the preamble to, among other things, recognise Indigenous Australians that John Howard proposed in 1999 but which was accompanied by very little public discussion.

After the referendum

On referendum night I said the following:

“Now that the referendum is over Australia needs a time of reflection before we consider our next steps on the reconciliation journey.

We need each other. We belong to each other. We share this land and we must walk together so that we can close the gaps between us.

On Monday, Parliament returns. My hope is that during the siting week we will recommit to the path of reconciliation. That is what all Australians, no matter how they voted, expect of us.”

It is almost 10 months since the referendum.

As I said, it was my hope that the Parliament would resume and the government would seek a resolution of the Parliament reaffirming our commitment to reconciliation in the wake of the referendum defeat.

No such resolution has been moved.

That is a shame because the failure of the referendum derailed the reconciliation process.

But what is more of a shame is the national silence on Indigenous affairs that has followed since the referendum.

The Prime Minister has made only one significant speech – on the anniversary of the apology – on Indigenous issues since the referendum.

The Government didn’t have a Plan B. This is a tragedy.

Issues of Indigenous disadvantage which consumed so much of the public debate over the last few years have been hurried off the national stage.

In some respects, it is like the referendum never happened.

I won’t say I’m angry about the intertia and lack of focus and activity since the referendum.

I won’t say that because anger seems to be the go-to place for too many people in politics, and there is too much anger these days, but I am frustrated and profoundly disappointed.

It seems the conversation about our country and its Indigenous people was snap frozen on referendum day.

Too many people, too many groups, from the prime minister down have been overtaken by their own political and personal disappointments from the referendum.

Yes, for many of us who campaigned for YES we felt the loss – that happens when you lose campaigns, but that loss does not compare to the lived experience of failing health, family violence, inadequate housing and unequal economic opportunities.

At Garma in 2022 the Prime Minister said he would approach his task with:

“humility because over 200 years of broken promises and betrayals, failures and false starts demand nothing less [and] because – so many times – the gap between the words and deeds of governments has been as wide as this great continent.”

But the referendum was a false start and the Government’s deeds since the referendum have not matched up to their words.

It’s time for everyone, including the Prime Minister – especially the Prime Minister, as well as Indigenous leaders and the country itself – to get back to work on Reconciliation.

It’s time for everyone to dust themselves off and get back to work.

The Voice is past, but the challenge of making our country stronger and more united remains.

And that work is even more pressing today than it was a year ago.

With no disrespect to anyone, our country cannot afford another wasted year. All of us have to engage again in this shared work.

Silence, ignoring each other, is not a strategy for national success.

My challenge to the Prime Minister is to outline how he is going to address the practical issues that affect Indigenous Australians that remain unaddressed since the referendum.

Throughout the campaign, the Prime Minister rightly spoke with passion repeatedly about the need to close the Gap throughout the campaign. In a speech to the Australia Israel Chamber of Commerce, he said:

The status quo is a chasm between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australia.

Just consider the facts. Indigenous people have an eight-year gap in life expectancy, a suicide rate twice as high, and rates of disease and infant mortality and family violence so much worse than those of the general community. Something that shakes me is that young men are more likely to go to jail than to go to university. In 2023.

They have among the worst incarceration rates in the world. Only four out of the 19 Closing the Gap targets are on track. 4 out of 19.

These figures are a call-out to all of us to make this a national priority.

Australians can do more than one thing at a time – and that very much includes the Government.

And yet in the post-referendum world, the government has not capitalised on the renewed consensus that existed on the need to close the gap.

Despite its failure to carry, the referendum had the effect of engaging many Australians on Indigenous issues, perhaps for the first time. Whether they marked YES or NO on their ballot papers, many voters were prompted to consider the reality of Indigenous disadvantage and the need to address it.

The tragedy however, was that this consensus on Indigenous disadvantage, common to both sides of the referendum debate, has not been harnessed for the public good, post referendum.

Let me take a couple Indigenous issues on which the government could have acted since the referendum.

The first is rheumatic heart disease. This is a health condition affecting many Indigenous communities which Noel Pearson raised many times during the referendum campaign. Sadly, there has been no inquiry or any focussed efforts to deal with rheumatic heart disease in Indigenous communities since the referendum.

A second is addressing that statistic that the Prime Minister said shook him – that an Indigenous boy is more likely to go to jail than university. He repeated this often in his advocacy as did many others.

The need to reduce the disproportionate rates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander incarceration was raised in the latest Closing the Gap report. Yet unfortunately, the latest data from the ABS reveals that Indigenous incarceration rates have increased. In the March quarter 2024, the imprisonment rate for Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders was 2 591 persons per 100 000, up from 2418 in the March quarter 2023.

On the related issue of university completion rates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians. According to findings from Universities Australia, Indigenous Australians have a completion rate of just 47% compared to 74% for non-Indigenous Australians. Universities Australia has noted that only 7% of young Indigenous Australians have a university degree compared to almost one in two non-Indigenous Australians.

Enough time has passed since the referendum for the government to focus on the Indigenous issues that many Australian heard about for the very first time. It is time for the government to get back ‘on the horse’ and focus on addressing those closing the gap issues which were highlighted in the referendum.

With today’s announced retirement of my friend, the Minister for Indigenous Australians, Linda Burney who is the first Aboriginal woman elected to the House of Representatives, and who I acknowledge as someone who cares deeply about advancing reconciliation and closing the gap, the Prime Minister is presented with an opportunity.

The Prime Minister should use the occasion of a ministerial reshuffle to work with the incoming Minister for Indigenous Australians to reset and recommit to tackling the issues facing Indigenous Australians that have been aired for many years, and particularly throughout the course of the referendum debate.

In combination with closing the gap there needs to be a re- commitment to the process of reconciliation.

The ANU Centre for Social Research and Methods post-referendum survey found that 79.4% of Australians think that the Federal Government should help improve reconciliation.

Perhaps such a recommitment involves motions in the Parliament or community activities like the walk across the harbour bridge for reconciliation in 2000.

Whatever form it takes such a process must engage Indigenous leaders and other prominent Australians that were from both the YES and NO sides of the referendum. Unless that happens, then it is not true reconciliation.

In the journey to reconciliation, I envision a key public role for the Catholic Church. The Church has so much to contribute to the cause of reconciliation with its practical experience of working with Indigenous communities, its abiding belief in human dignity, and its commitment to the subsidiarity principle.

To conclude, the new pathway to reconciliation is unlikely to entail constitutional recognition, but this does not mean we should give up on reconciliation. We must find a new course by listening to Indigenous people and working out a pathway together.

In the words of Archbishop Peter Comensoli “Walking together will occasionally be hard-going, but in the end it will be worth the trouble.”

I promise to continue on the shared journey to reconciliation. Although the path is now different, the destination remains the same.