With the release of the codesign report by Tom Calma and Marcia Langton, advocates for a Voice for Indigenous Australians need to shift their efforts. The key issue at stake now is not words in the Constitution but whether it will genuinely give voice to Indigenous people on the issues that affect them most. We must take the time to get the local and regional bodies right — they are essential to what the Voice is about.

We know the statistics. The gap between the outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians and other Australians is far too wide, whether on health, employment, education, incarceration or life expectancy. We can keep wringing our hands about it or ask ourselves some questions about why, time and again, smart people of goodwill from both sides of politics fail to shift the dial.

The truth is there is such a gulf between what seems like a good idea in Canberra, in a university or think tank, and the reality of life in community. Too often no one really speaks to those in community to find out how to change things on the ground.

That is why the Uluru Statement — and the concept of the Voice that came from it — ranks as a watershed moment. Uluru was Indigenous Australia’s call to be consulted on the policies and laws that affect them.

For some, Uluru went too far. For others it was too modest. Wherever you sit, Uluru’s effect on the debate about Indigenous affairs was momentous.

At the time of Uluru, there were competing visions of what the Voice might look like. One version proposed a national body providing advice about law and policy in a parliamentary context. Another envisioned local communities establishing bodies to deal with government about issues they face. While consultation was always the aspiration, what the Voice meant in practice remained elusive.

In 2018 I was appointed with Labor senator Pat Dodson to lead a committee to put “meat on the bones” of the Voice and to reconcile the competing visions. We proposed Indigenous consultative bodies be set up on a local, regional and national basis. The bodies could be a vehicle for government to test policy ideas, their design and implementation, with those directly affected by them and for Aboriginal people to bring issues to government.

Despite the popular conception, and the power given to it in 1967, the federal government is not responsible for much that happens in the lives of most Aboriginal Australians. These matters are still largely the province of the states and territories. Like almost every other area of policy, the commonwealth is just the ATM.

It is not surprising the committee Pat Dodson and I chaired found the idea with the strongest support among Indigenous people was local and regional Voice bodies. Most people in communities don’t care about Canberra, but they do care about the rules that affect their children’s education and their ability to access services. As we said in the report: “We have listened closely to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Discussion has highlighted that the majority of day-to-day challenges facing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples do not fall within the ambit of the national parliament. Many of the solutions to these challenges are at the local and regional level.”

Ian Trust, from the Wunan Foundation in the Kimberley, told us the success of the Voice “would be measured by the impact it would have for people in local communities”. Alf Lacey, mayor of Palm Island Aboriginal Shire Council, said: “Not all of us have got the ear of the parliament. I think of a regional framework that allows us living in regional Australia, particularly northern Australia, to have some meaningful dialogue and input into the future of our community.”

We also noted that to work properly the bodies would need to be designed by local communities, reflecting local practices and not duplicating bodies already operating successfully. This could not be another Canberra diktat.

This was why we recommended a process of Voice codesign jointly led by Indigenous people and government. This would be modelled on the successful consultation processes Charlie Perkins undertook a generation ago. He sat on the ground in community after community asking Aboriginal people how government could better engage with them.

Today, we are part way through that process and an interim report has been delivered. What should concern advocates of the Voice is whether or not Indigenous Australians will be adequately heard through what is proposed. There is good reason to believe much more work needs to be done. In August 2019 Labor shadow minister Linda Burney travelled through Central Australia and reported that people in remote communities had not heard of the Voice. A renewed effort is needed to focus on the local and regional bodies, particularly in the more than 1200 remote communities. Ken Wyatt said he wants as many Aboriginal people consulted in the months ahead as possible, stating: “The government is particularly interested in ensuring that any Voice structure in its final form leads to a greater say for Indigenous Australians on matters that affect them and real changes on the ground.”

If local and regional bodies are not established on a firm footing it will undermine the legitimacy and utility of a national body. It will be highly bureaucratic but disconnected to the grassroots.

COVID makes this process slow and difficult. But it is more important we get it right, than do it quickly. Any Australian who is serious about the concept of the Voice needs to focus on this part of the process.

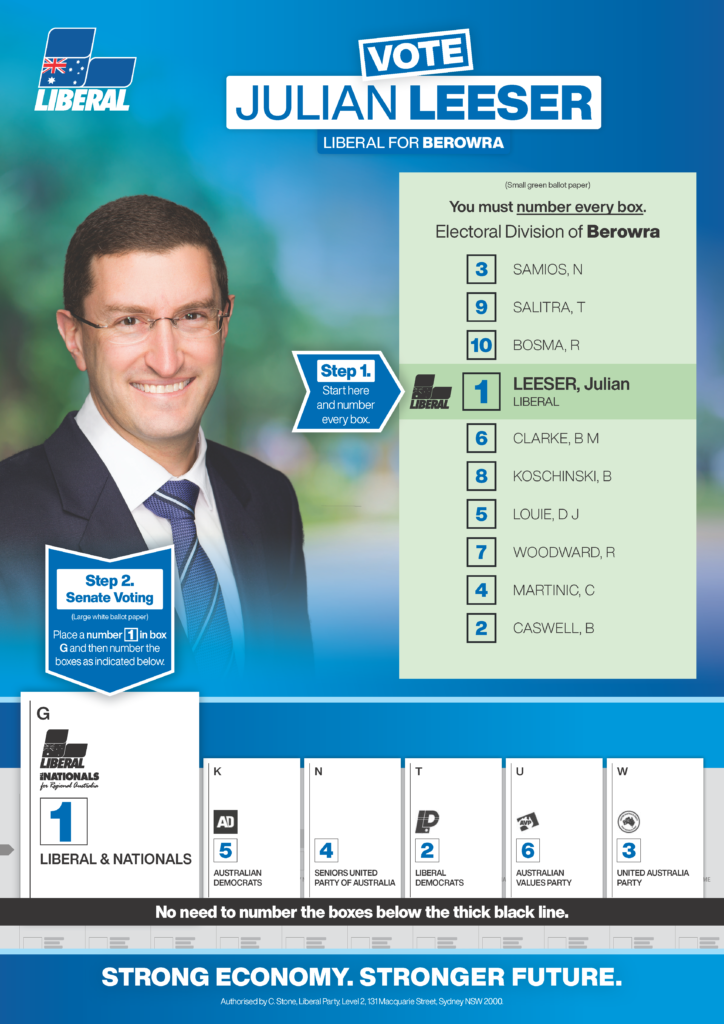

Julian Leeser is the federal member for Berowra in NSW.

This article was published in The Australian on the 20th January 2021.